A N N H O L Y O K E . O R G | A M E T H O D O L O G I C A L C A T A L O G U E O F W O R K S

20 | S E T

Aleatoric ensemble, 1990/91

Wall panel of painted wood with brass fittings, 191 x 389 cm

Fifty-four panels of painted wood, movable and removable, each 30 x 20 cm

Steps of painted wood and linoleum, 75 x 90 x 30 cm

Rubber-tipped brass rod, length: 100 cm; diameter: 10 mm

Sammlung der Berlinischen Galerie, Landesmuseum für Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur, Berlin [ Collection of the Berlinische Galerie, State Museum for Modern Art,

Photography and Architecture, Berlin ].

As the title of what I’ve termed an aleatoric ensemble, I used the word “set,” for it possesses many meanings and is presentable in many languages. Indeed, even the

French use it with impunity to denote le set in a game of tennis, as well as le set in the sense of a film-stage and its properties. “Set” in English can, of course, mean just

about anything; it is the most complex word in the entire Oxford English Dictionary. As a noun, it signifies everything from the direction of a tide or current’s flow, to the setting or

decorations for the staging of a ballet, opera, theater play or film, right on down to a simple deck of playing cards, or, in typography, the amount of spacing in typesetting—and hence the

distance between letters—as well as the width of a single piece of type, or of an individual character. As a verb, it is virtually unstoppable, and—like its rhyming kinswoman “get”—maddeningly

versatile in combination with a plethora of adjectives, nouns, and prepositions.

In the work I titled SET, fifty-four wooden panels—each measuring 30 by 20 centimeters and painted the very palest of greys—can be hung, turned over, and rearranged on, or removed from, a wooden wall unit, which has been divided into one hundred and eight fields—twice fifty-four, or six by eighteen, that is—and coated with glossy deep-red enamel paint.

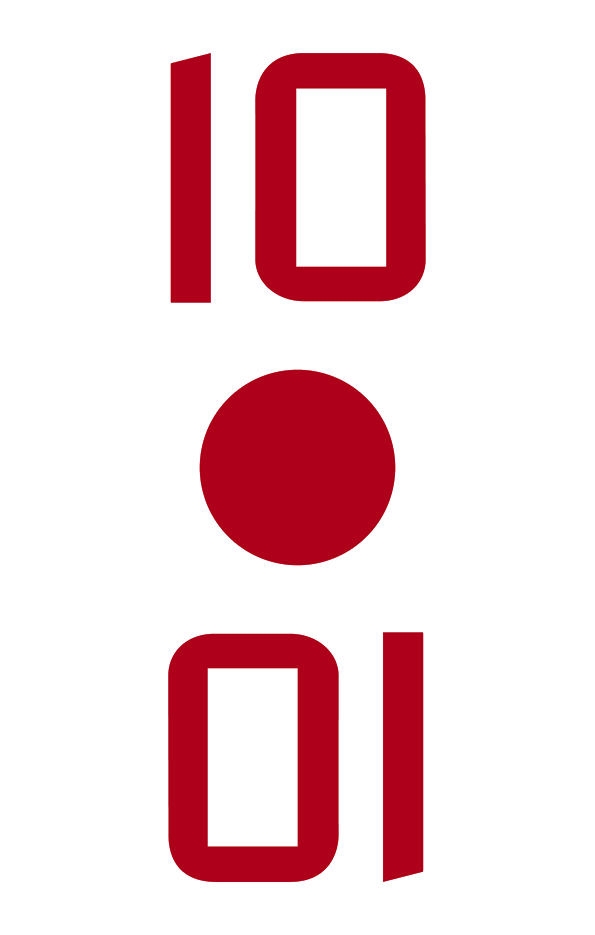

Three arrangements of the aleatoric ensemble SET’s wall unit (simulation), 191 x 389 cm, 1990/91: all card backs; card backs

and faces; all card faces.

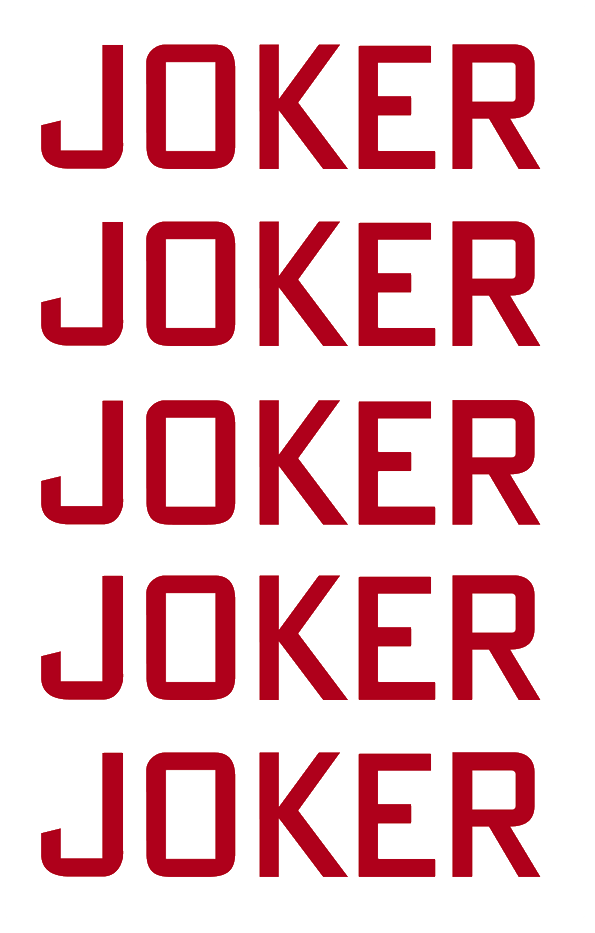

On the front and back of each small grey panel, the back and face, respectively, of a playing card made of lacquered wood is mounted, so that a full French deck of cards is represented—including two jokers, the “joker” being a 19th-century US-American novelty introduced with the rise of the game of poker—and hence all the combinatorial possibilities essential to a game of cards suggested.

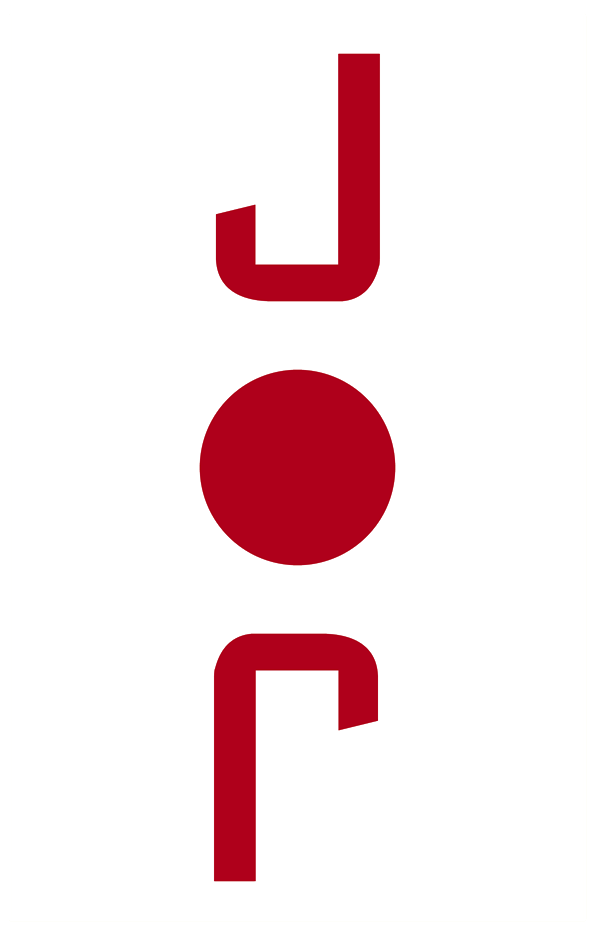

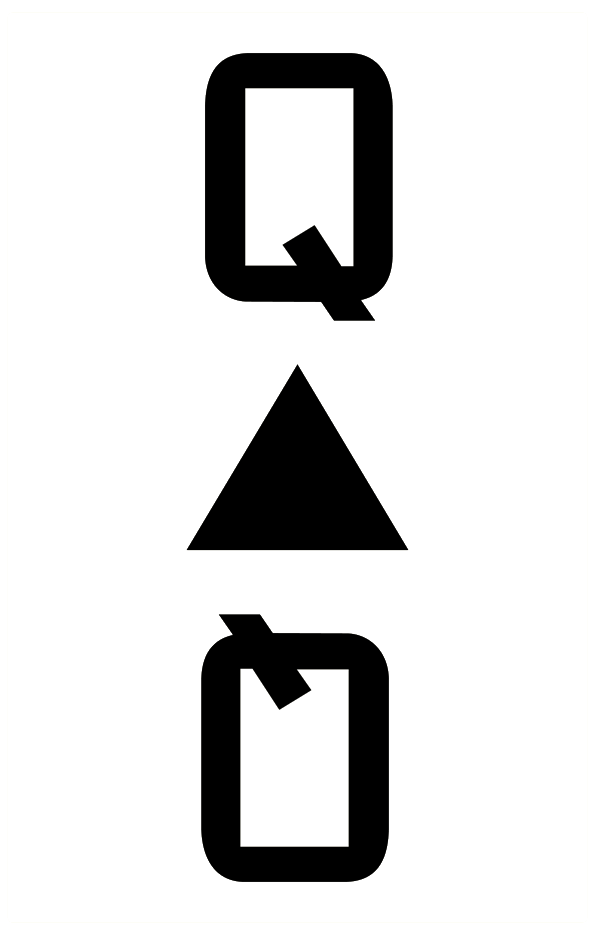

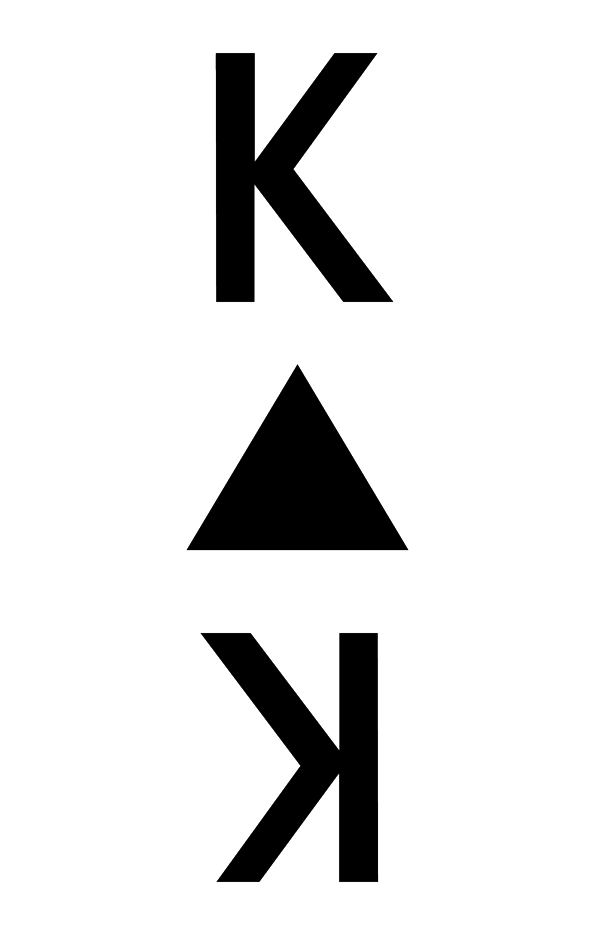

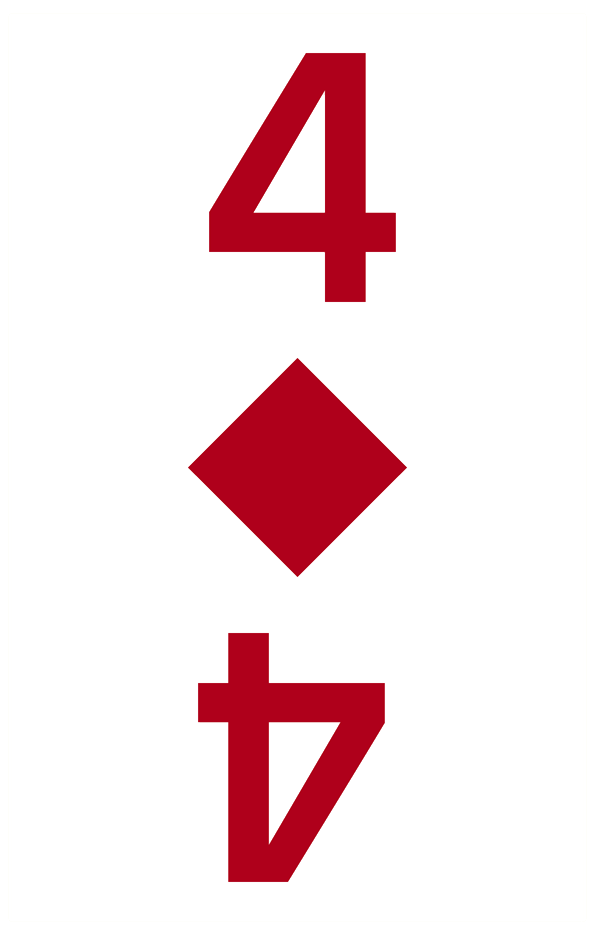

The motifs on SET’s playing cards. Copyright © 1990 Ann Blum.

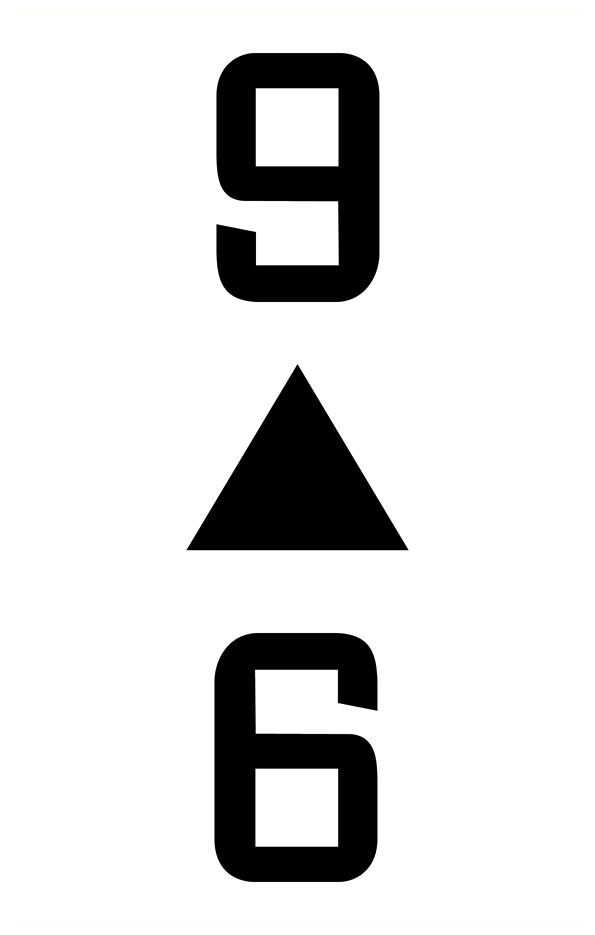

Decorated using glossy acrylic paint, so as to resemble very small enamel signs, and one-to-one in size with those belonging to a legitimate, pasteboard deck, the individual playing cards are fashioned out of a very thin plywood used, for example, to make model airplanes: a material consisting of just three layers of veneer and but 0.6 millimeters thick. A black rectangle is painted on the back of each card, leaving a white, five-millimeter-wide border around the edges. The value of each card is represented on its face by a letter, for “face,” or “court,” cards and aces, or a number (for “pip” cards), while its suit is indicated by a geometric form: red circle (lighter in shade than that of the supporting wall) represents “hearts” ; a red square standing on one corner stands for “tiles,” or “diamonds ”; a black equilateral triangle on its base equals “pikes,” or “spades” ; a black square on its base is the symbol for “clovers,” or “clubs.” The four-millimeter stroke of the letters and numbers I designed for the piece—together with their width (16 mm) and height (24 mm)—provides a module for the dimensions and proportions of SET’s individual component parts and of the ensemble as a whole.

SET at the Berlinische Galerie, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, 1992. Photo © Hermann Kiessling.

A set of small, freestanding wooden stairs—painted black, with their steps inlaid with black linoleum—stands before the red wall unit. A brass rod, tipped with black rubber, lies atop the stairs, so that, even as a static tableau, SET suggests the inherent variability of each particular situation: the possibility for each viewer to influence the composition and the game, according to his lights.

I, for my part, would be for playing “Concentration”—also known as “Memory”—as I so vividly recall doing with my mother on at least one dark afternoon when I was very small . It was too wet to play outside, and we spread out a deck of cards, face down on the carpet in the living-room, and set to work remembering.

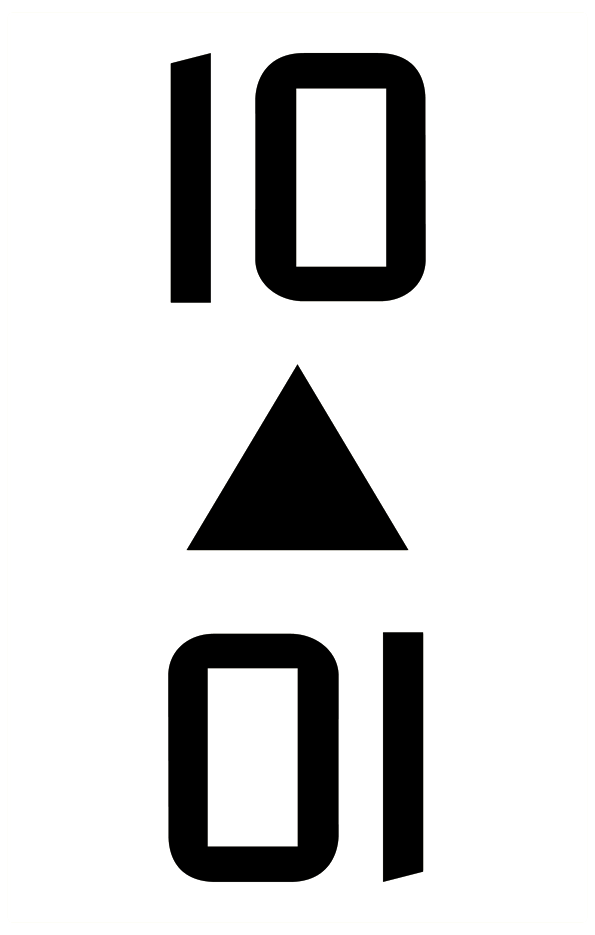

Turning over SET’s playing cards.

A work like SET does not reproduce existing objects, nor does it depict them; it is those objects’ re-presentation in another light. Yet, as I was developing my aleatoric ensemble, I did toy with the idea of making something utilitarian (or at least usuable) and introducing it into daily life, to wit, I wanted to have a deck of cards, based on the one I was designing for the piece, printed and packaged in series, and then marketed as ordinary playing cards. For lack of production means, however, nothing ever came of the project, but I’m sure that, somewhere in an old notebook, I have the calculations I made at the time, including a break-even point for this uncharacteristically entrepreneurial scheme.

All of the notes in that notebook were made in Worpswede, a small town northeast of Bremen, where Blum and I both had a residence stipend. We shared a one-story,

semidetached apartment-cum-atelier, whose floor-to-ceiling plate-glass windows gave us a clear view of the Teufelsmoor (“Devil’s moor”) nature reserve: a large stretch of the bleak and boggy

landscape for which the area is renowned or, as some would surely say, “notorious.”

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this village had been the center of a well-known artists’ and writers’ colony—the town’s art nouveau

station-building-now-turned-restaurant, for instance, was designed in 1910 by Heinrich Vogler, a prime example of the group’s artistically multipurpose members—and today, Worpswede’s raison

d’être is still, indeed its name is synonymous with, its reputation as the cradle of once-advanced aesthetic and communal-living norms. “Art” represents its only industry—cottage or otherwise—and

there’s not a shop in town whose offerings refrain from playing on the word in one form or another. It was here that I computed the costs for my decks of cards, worked out the plans for SET,

and—as one of our obliging neighbors had a motor-driven miter saw—where I accomplished the preliminary woodworking for the piece’s fifty-four small movable panels.

From early December 1989—barely a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall—until August 1990, driving the old Fiat we’d bought

three years earlier to be able to accept another “retreat” grant, in a hamlet far remoter, we regularly traversed the four hundred kilometers between Worpswede and Berlin—always following the northernmost of the three transit routes from West Berlin to West Germany. The first time we crossed the border,

that winter, everything—the dire warning signs ; the guards ; the lines of waiting cars ; the conveyor belts that invisibly moved one’s passport and other pertinent documents to where, a few

meters farther on and with, at best, a grudging grunt, they were finally returned, so that one could leave the checkpoint and be on one’s way—all this had still been in place. Each time we made

the trip during the next nine months—with every crossing of the border, that is—something more had been eliminated from the procedure’s irksome props and protocols, until at last, come summer, we

looked in vain for anyone in uniform to mark our passing.